Temperance Movement's rise and fall is a sobering tale of how good intentions can lead us astray – Susan Morrison

When I was young, they were a familiar sight on street corners outside pubs. Firebrand preachers in front of Temperance banners, perhaps a wee band of hymn singers, banging tambourines for sobriety. When kids like me pledged to deny the demon drink forever, they gave us sweeties, which addicted us to sugar and raised the possibility of future diabetes.

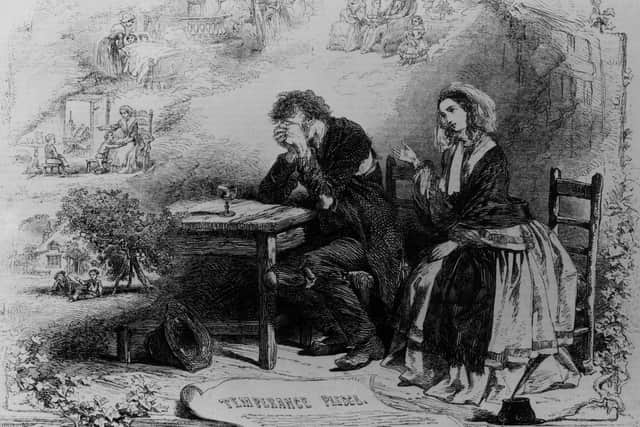

My parents would smile and shake their heads. Temperance was a busted flush even in the 70s, but once it was one of the most powerful movements of 19th-century Scotland, and it had a global impact in the 20th. Victorian Scotland had an issue with drink. No doubt about that. It was a tough place to live and work. The men building the canals, working in the iron mills and down in the mines drank away their pain, the poor to ease the misery. We’d call it self-medicating now. We still do it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn Dunlop was a Scottish landowner and a bit of a traveller. He’d noticed that drinkers in foreign lands didn’t degenerate into the sort of drunken rabble he’s seen back home. This observation will be familiar to anyone who has seen a Paisley stag-do abroad.

The problem, he reasoned, was the whisky, which saturated every Scottish occasion, from christenings to funerals. And so, with his aunt, Lillias Graham, they set up the first temperance society in October 1829. They were based in Maryhill, once the family estate of the Grahams. In fact, Mary Hill was named after Lillias’ mother. They were not anti-drink. The name of the new movement was temperance, not abstinence. ‘Strong spirits’ were the enemy, not beer.

It was a mammoth task. The drinking habits of the Scots had international notoriety. In 1853, a snippet in the Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer, noted that “an elegant little controversy has been going on recently among the Scotch people, as to which portion of them may be considered the most addicted to drunkenness… which city has the greatest tendency to intoxication”. Edinburgh, Dundee and Glasgow are nicknamed “Drunk, Drunker and Drunkest”. Obviously Glasgow won the fight. And this from Australia. The shame.

Dunlop took advantage of new technology to grow his movement. The railways carried his message throughout Scotland and printing powered the drive to empty the pubs. One of his earliest allies was William Collins, founder of today’s mighty Harper Collins publishing empire. He had started in a Dundee mill and was horrified by the inebriated mill girls. They really put the stuff away, according to the police arrest records of the time. They still can. Collins, however, was no temperance man. Abstinence was the only way.

The two parted company eventually, but temperance, which increasingly became straightforward abstinence, grew throughout the 19th century. The most ardent foot soldiers were the women. They watched their men drink the money that should have been feeding the family. They had no vote, but they could influence local councillors, smash up illegal bars and raise funds to hold temperance rallies. Women across the class barriers met, planned and organised. All of which went on to pay dividends for the later battle for women’s suffrage.

Temperance washed over Scotland. The tea room became a rival to the saloon bar. It was possible to eat in temperance restaurants and take temperance holidays with Thomas Cook. When the great abolitionist Frederick Douglass came to Edinburgh, he stayed at the York Temperance Hotel, on Nicholson Street. Many such hotels had a bottle of whisky under the front doorstep, so guests could crush the demon drink underfoot on the way in.

Temperance took on brewers, distillers and politicians throughout Victoria’s reign, but possibly its greatest triumphs lay in the 20th century. They got barmaids banned from Glasgow pubs in 1902, and in 1913 the Temperance Scotland Act allowed for referendums to be held that enabled districts to shut the bars down. Places like Cambuslang, Kilsyth, Airdrie and Stewarton voted to go ‘dry’ in 1920. Kirkintilloch stayed pub-free until 1967.

But for Lady Temperance, the crowning glory lay across the Atlantic. Throughout the 19th century, strong links were forged between the movements of Great Britain and the United States. The abstinence sisters of America learned much from the tea-total women of Scotland, and not just the words to fine temperance hymns like Yield Not To Temptation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey too were powerless at the ballot box, but they campaigned relentlessly to get ‘dry’ candidates onto the ballot sheet. They got their men to vote them into government and in 1919 their wildest dream came true. The Volstead Act banned alcohol across the United States. An entirely dry nation. The people of America, the temperance leaders assured their followers, would thank them for this paradise on Earth.

It was a spectacular own goal. Hundreds of thousands of jobs vanished as breweries, bars and restaurants closed. The United States Treasury lost more than $11 billion in tax revenue, whilst shelling out more than $300 million to enforce an unenforceable law. Millions of ordinary people became law-breakers, as everyone knew someone who could get their hands on bootleg gin or whisky. Those bootleggers became as wealthy as Columbian drug cartel leaders. No one is sure how many went blind or died drinking dodgy booze. Americans actually drank more.

There was also a dramatic increase in the number of self-professed rabbis when people discovered that clerics could get wine for their ‘congregations’. Franklin D Roosevelt ended prohibition in 1933. When he signed it away, he is reputed to have said: “I think this would be a good time for a beer.”

Funnily enough, John Dunlop would have agreed with him. And no, I didn’t keep the pledge. Perhaps I should give the Sour Plooms back.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.