American Civil War: How Clyde shipbuilders helped Confederate forces run the Union blockade – Susan Morrison

The wreck of a Victorian paddle steamer lies just off Gourock – 55° 57.912'N, 004° 47.212'W, to be precise. She’s about 28 metres down, her stern pointing to Helensburgh. Divers today can still make out the paddles and parts of the engines. She had hoped to cross the Atlantic, and around the wreck there are mounds of coal, fuel for the voyage.

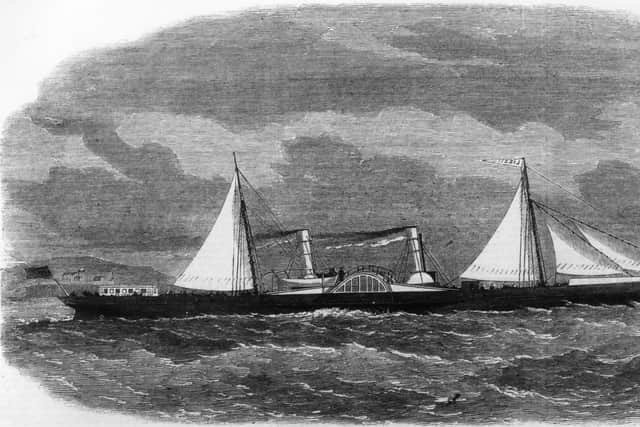

Her name was Iona. She’s actually designated as “Iona 1” today. When James & George Thomson launched her in 1855, she was seriously good-looking. Twin-paddled and twin-funnelled, sleek and fast, she was such a hit with the Going Doon the Watter crowd they nicknamed her “the Queen of the Clyde”, but she carried her last paying passenger in September 1862, and then she changed hands. She changed decor, too. She was painted grey. Harder to spot, like she had something to hide, perhaps the identity of her new and faintly mysterious owners.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn October 2, 1862, she weighed anchor in Gourock Bay and headed for the Bahamas. She was sailing at night, which wasn’t unusual. The brand-new steamer Chanticleer was also at sea that evening. She'd been undergoing speed trials. She was heading home, and passed the Cloch lighthouse just before seven o'clock.

Minutes later, the Chanticleer ploughed into the Iona, running her over. She sank quickly. The crew were lifted off safely, including a stowaway, who presumably thought better of a life at sea after his close escape. The Chanticleer claimed the Iona swung into their path. The Iona claimed the same of the Chanticleer. The crew of the Iona was accused of being drunk. The Chanticleer’s crew had accusations of dangerous sailing thrown at them.

No matter. The Iona was now on the sea bed, and her shady owners were deprived of the sort of fast, sleek, shallow draught ship they needed. The erstwhile Queen of the Clyde had been destined to run the Union Navy blockades of the Confederate States of America.

The wreck of Iona 1 tells a story of Scotland’s complicated involvement in the American Civil War. Prior to the Confederates firing on Fort Sumter in the summer of 1861, the South almost prided itself on being free of nasty, smelly industry. Northern Yankees went in for that sort of thing.

In the novel Gone With The Wind, written by a woman steeped in the tales and history of the war, her hero Rhett Butler causes a stooshie at the Wilkes’ home by puncturing the posturing Southern good ol’ boys with his observation that there were no factories or armouries below the Mason-Dixon Line.

The South had to buy in its guns, medical supplies, and even steel. They also had to get their cotton out to fund the war effort. The Union quickly slung a blockade around the major Southern ports, which steadily tightened its grip. Fast manoeuvrable ships were needed and, at the height of Victoria's reign, there was one shop for ships that fitted this bill. Clydeside.

Nominally, the UK was staying out of the Civil War, a mild shock to Southerners who thought that the home of the cotton-hungry mills would naturally back their cause. The slave-owning issue, they felt, was something Her Majesty's Government could come to terms with, which totally overlooked Her Majesty’s known distaste for the practice of enslavement. After all, her late husband had given his first-ever public speech to the Emancipation Society, and Victoria was known to take on Albert’s causes.

Strictly speaking, selling ships to the Confederacy was frowned upon. They were most definitely not keen on the building and selling of armed vessels. Some got around this issue by building what looked like ordinary steamers, but had them armed at sea. Ordinary trading vessels, well, that was a grey area.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe shipbuilders and owners knew selling to the rebels was a tad risky. They were also fully aware that the Confederacy was fighting to preserve the right to enslave human beings. Some in Scotland were actually sympathetic to the cause. And there did seem to be a lot of Confederate gold available to buy clapped-out steamers, or better, build new ships for their Southern friends at vastly inflated prices.

Take the Agnes E Fry, originally called the Fox, launched in March 1864 by Greenock’s Caird & Co. Her new captain, Joseph Fry of the Confederate navy, renamed her after his wife. Lovely idea, but it didn’t do the ship much good. She went down off North Carolina in December of that year. Her wreckage was found in 2016.

Dr Eric Graham, in his groundbreaking book, Clydebuilt; The Blockade Runners of the American Civil War, makes no bones about it. Ships bought and built on the Clyde were a lifeline to the rebel states. He estimates that over a third of the steamers running the blockade were Clyde-built. The boom continued at sea. Fortunes were to be made by the skippers and crew who didn’t have many scruples when it came to the horror of slavery.

When Margaret Mitchell wrote her blockbuster novel, she chose her hero wisely. Rhett Butler is still a by-word for glamour and derring-do, even today, when we tend to look at Gone with the Wind with more critical eyes.

We never actually see Rhett at sea, but the inference is clear that this hero of the Confederacy slices through the blockade, running rings around the Union forces, all the while sporting that insouciant Gable grin.

Margaret implies that Rhett sailed a schooner, and probably had romantic images of billowing sails under the moonlight, but the truth is that had Rhett Butler existed, he would probably have captained a Clydebuilt steamer, one of our history’s more inconvenient truths.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.